A long friendship, like no other

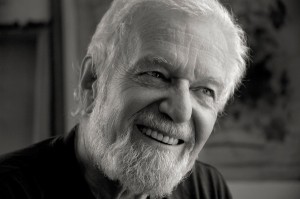

Alan Glass portrait by Daniel de Laborde©

Montreal, Canada, 1932

Cdmx, México, 2023

Alan was first and foremost my great friend, and over the course of forty years our relationship deepened, moving from mutual trust to always fantastic conversations that could last from a few minutes to several hours. These exchanges deepened my understanding of the values of life, the art world, the sensitivity of things and the appreciation of people.

Alan was always very secretive and fair-minded, with a unique ability to collaborate, listen and be respectful of ideas. He was the epitome of noble. I was always amazed by his capacity for wonder, the child he was and the freedom of his thought. Everything interested and entertained him. But the most important thing was his work, to which he devoted many hours of his days and nights. Alan knew how to enjoy everything.

Born in 1932 in St Bruno near Montreal, his father was in charge of the Mont Bruno golf course, which his uncle had designed. His mother, of Scottish origin, was devoted to her children and husband. Unquestionably his greatest admirer and accomplice. Alan had a hard time at traditional schooling, perhaps because the symmetrical shape and phonetics of a letter interested him more than the sign. His logic and intelligence led him to make up for lost time and discover his vocation by studying at the École des Beaux-Arts of Montréal, where he met his great mentor and lifelong friend, Alfred Pellan. Pellan had returned to Canada after fourteen years in France. He was one of the founders of the Prisme d’Yeux movement, which represented a break with traditional, religiously-inspired art in Canada. No doubt his conversations with him led Alan to expatriate at the age of nineteen to Paris, where he arrived with a modest grant of a thousand dollars from the French government and all the energy he needed to conquer the world.

In Paris, he attended the Beaux-Arts and worked at a series of odd jobs for ten years. He went from cleaning chandeliers at the Peruvian Embassy to boxing suppositories with his friend Jodorowski, then to packing books in a bookshop. In 1956, he became a doorman at the Club St-Germain, where the best jazzmen of the day performed. In his little alcove at the entrance, he made drawings with a Bic, which would later be assimilated into the world of the Surrealists, and which Breton would go on to exhibit at Eric Losfeld’s gallery, Le terrain Vague.

Alan took the chance to travel around Europe and France, accumulating thousands of objects that would one day find their way into boxes created with poetry, romanticism and fabulous creativity to link them together. His memory and capacity for association led him to create these unique works. In his room at 5 rue Manuel, where he lived during his ten-year stay in Paris, he also had the opportunity to paint his “invisible pictures” that lifted him to the heavens. However, Alan didn’t talk about his painted or engraved work. Only the automatic Bic drawings were the subject of conversation. Alan had lost sight of them for over sixty years, until on his eighty-eighth birthday, he found a letter in his mailbox that had traveled ninety days from Grondines, Canada. Micheline Beauchemin’s generous heir, Jean Paul Parre, had sought him out to tell him that he had found his drawings, safe from the weather that would have damaged them.

After the pandemic, we travelled in search of the drawings, which coincided with the Indian summer season, of which Alan had vivid childhood memories. Alan took the opportunity to visit his various friends, with whom he always kept in touch by letter and, later, frequently by phone on Saturdays and Sundays. He was full of energy, no doubt due to the joy of having rediscovered this work, a fundamental element in his artistic development. With the recovery of his drawings, Alan felt a kind of peace, because he couldn’t believe that a part of his artistic development would be lost. He decided to make a second book with these drawings.

In 1962, he decided to settle in Mexico, a country that welcomed him with open arms and where he would continue to work for over 60 years, exhibiting in the Antonio Souza and, later, Pecanins galleries, while some of his works would become part of major collections and museums. Alan continued to rummage through his thousands of objects that ended up in boxes, the genre for which he became best known. He now had numerous workshops in his house in the Roma district and worked frantically to arrange his objects as he did on a daily basis. He also left clues to the interpretation of his work, that he never showed, as well as indications for understanding his oil and watercolor paintings that one day Salvador, his great friend and supporter for over 40 years, would show us. He knew that we would find them, and that we would thus have some final references for deciphering “the path of his work”. He warned us that we would need a lot of time to meet this challenge.

Alan passed away on January 13, 2023 at his home, having worked until two days before. With his last strength, he gave me a farewell hug I’ll never forget.

In 2024, to mark the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Surrealist Manifesto, a retrospective exhibition will be held at Bellas Artes, Mexico City’s Museum of Fine Arts, and another at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Carlos de Laborde-Noguez

Mexico City, January 16 2024